A Glossary Of Words My Mother Never Taught Me

Conversation 31.01.2020 19:00

With Renée Mboya and Candice Breitz, co-hosted by Forecast

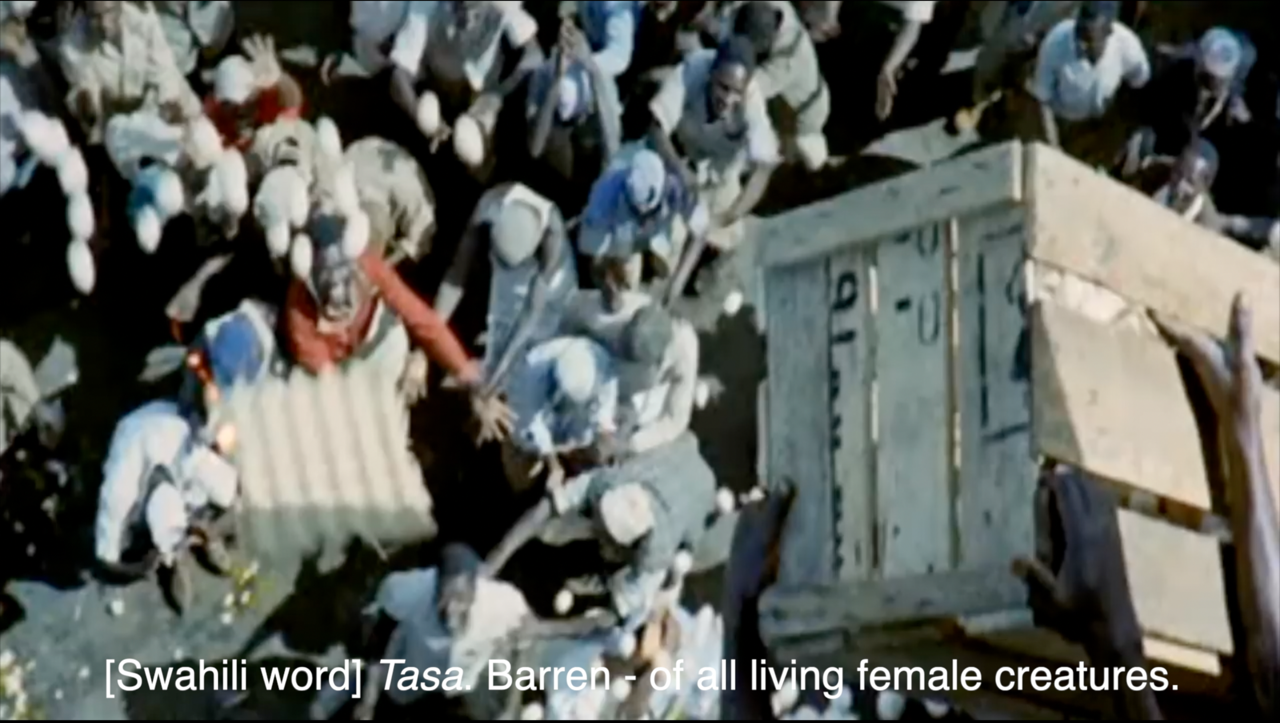

Renée Mboya is currently developing filmic reflections on mondo films that were made about Africa between 1960 and 1992, observing this sensationalist form as a way to question the place of media and film in the heritage of learning and representation. Africa Addio is one such mondo film, produced and edited in 1966 by the Italian filmmakers Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi, the so-called masters of the mondo film genre. It has been described as the "ugly bastard child of the documentary and the peepshow.” Combining horrifying images of rampant violence with a glib narration, the film presents a narrative of post-independence Africa that bemoans the end of colonialism and speaks with explicit nostalgia about the loss of the "old Africa":

The old Africa has disappeared. Untouched jungles, huge herds of wild game, high adventure, the happy hunting grounds-those are dreams of the past. Today there is a new Africa-modern and ambitious.

The old Africa died amidst the massacres and devastations which we filmed. But revolutions, even for the better, are seldom pretty. America was built over the bones of thousands of pioneers and revolutionary soldiers, hundreds of thousands of Indians and millions of bison. The new Africa emerges over the graves of thousands of whites and Arabs, millions of blacks, and over those bleak boneyards that once were the game preserves.

What the camera sees, it films pitilessly, without sympathy, without taking sides. Judging is for you to do, later. This film only says farewell to the old Africa, and gives to the world the picture of its agony...

Heir to the patently fake travel and exotic “adventure” films produced by Western cinema between the 1920s to 1950s, which combined field material with staged studio scenes, mondo films constituted a ”cinema of attraction”’ that blurred fact and fiction and appealed to a "voyeurist pathology” (Goodall 2006). As a form, they promise the viewer a glimpse into the supposedly "previously hidden" and forbidden "cultures" of ‘others' without explicitly articulating – let along questioning – the cultural and social hierarchies that generate and validate the viewing subjects such films they imagined.

At precisely the moment when African nations sought to emancipate themselves from the west both culturally and politically, the mondo film offered a critique of otherness resplendently grounded in western concepts of primitivism, modernism, authenticity, representation, gender, class, race and identity.

During a period of relative western cultural uncertainty (i.e. the loss of empire), these films extracted, shuffled and reinserted its "others" back into the mainstream of western popular culture and imagination. In this way the mondo film was the antithesis of the ethnographic film – unconcerned with holism, context and authenticity – it relied on decontextualisation and on staging to create its effects. (Staples and Kilgore 1995)

Due to its epistemological uncertainty Africa Addio has much in common with a category of creative works that have been described as "para-fictional": para-fictional strategies are often less oriented towards the manipulation of the real and more towards the pragmatics of trust. With “varying degrees of success, for various durations, and for various purposes, these fictions are experienced as fact.” (Lambert-Beatty 2009)

Furthermore, the purported documentary status of the mondo film means that it can present a diverse audience with otherwise "forbidden" or socially unsanctioned material.

Renée is attempting to trace the cinematic roots of the mondo film, with specific attention to its portrayal of black/African bodies and various forms violence against such bodies. Her hope to move filmically between two extreme positions: one that gives credit to the film as an archive that can be used to further our understanding of the anatomy of atrocities enacted upon/within post-independence Africa; and the other that gives space to revisionist narratives which minimise and even refute the scope of the violence such representations portrayed. Africans “have always sought to master their past, have had their own historic discourses which render and interpret the facts of the past, placing them in an explicative and aesthetic frame producing the sense of their past” (Mudimbe and Jewsiewicki 1993).

In line with the mondo film’s long-established tradition of unauthorised edits, Renée’s proposed project is to re-edit/remake Africa Addio. She plans to use filmic techniques of censorship and propaganda that were active within cinema at the time of its making as a way to think about the film’s treatment and representation of bodies, the place of memory or the breakdown of memory in the creation of the filmic archive and in particular who the archive serves.

As of now, the result envisaged will be a 20-minute "truncation" enhanced – or obscured – by the use of black out screens, nonsensical word replacements, replacement and reediting of the original voice over and the reordering of scenes from the film i.e. using the techniques of mondo and para-fiction, appropriating the same footage that Jacopetti and Prosperi appropriated, to put forth a different narrative of Africa.

Renée Akitelek Mboya is a writer, curator and filmmaker. Her custom is one that relies on biography and storytelling as a form of research and production. Renée is presently preoccupied with looking and speaking about images and the ways in which they are produced but especially how they have come to play a critical role as evidence of white paranoia, and as aesthetic idioms of racial violence. Renée seeks to understand better the ways in which images are used to reinforce the institutionally manufactured narrative of the radicalised body as a constant danger to the law. Renée works from Dakar and is a collaborative editor with the Wali Chafu Collective.

Candice Breitz is a South African artists exploring – mostly in moving-image installations – the dynamics of how an individual becomes him- or herself in relation to a larger community. That group can be the immediate family, or real and imagined communities shaped by questions of national belonging, race, gender, and religion as well as the increasing influence of mainstream culture. Breitz holds degrees from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, the University of Chicago, and Columbia University in New York. She has been a professor at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Braunschweig since 2007. In 2017, Breitz represented South Africa at the 57th Venice Biennale (alongside Mohau Modisakeng). She has also participated in numerous biennials, triennials and film festivals allover the world.

Renée Mboya and Candice Breitz are currently participating in the Forecast mentorship programme. The event is an extension of Renée's work-stay with her mentor Candice which is taking place during the first two weeks of February 2020.